One of the questions we explore in our enquiry during the Legacy Book Workshop is “What advice would I leave future generations?” or, to say it differently: “What has life taught me so far?”

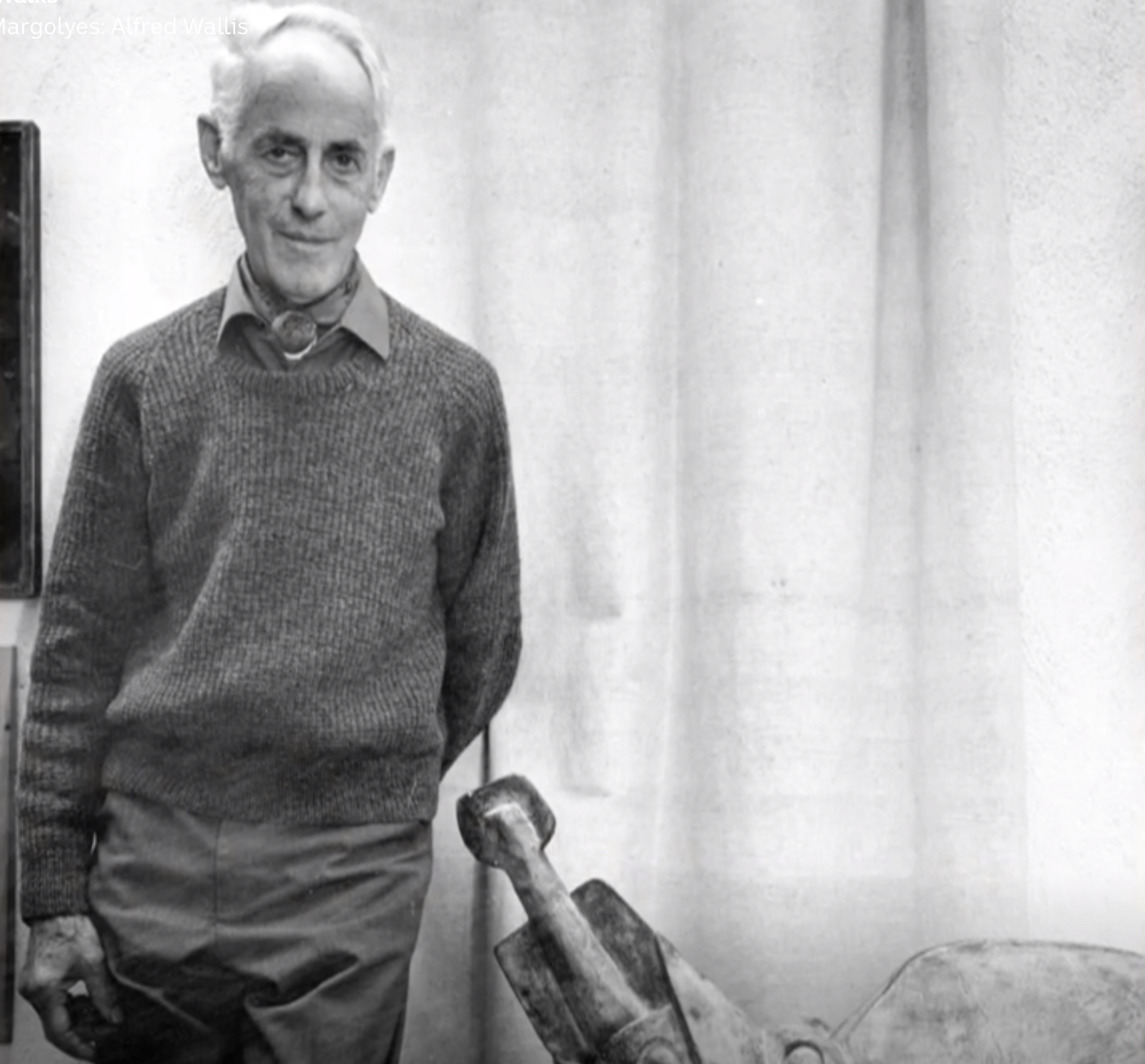

To illustrate this, I am going to tell a true story of an elder who made a lasting impression on my life story, Jim Ede, whose legacy includes Kettle’s Yard. His parting words to me when he was dying were “Be good.”

I was young, and wondered how after 93 years of life such simple advice could be his last words to me? More than 30 years later, his parting gift still resonates in my mind and heart. With my aging, those simple words keep taking on more meaning, and I am eternally grateful to him and his love for me.

Below is my story of one of our meetings:

Breakfast with Jim

Hanging on a string by Jim’s door, a wide flat cork with instructions to ‘Pull gently’ rang an old iron bell. I paused outside to look at the stones laid in gatherings which covered his window sills and made borders for his flower beds and lawn. Pebbles and rocks, eroded by time, collected on beaches over a lifetime: many Jim found on Tiree in the Shetlands. Piled together, they might have been washed up on another shore; yet they had found a place of rest here , in an Edinburgh terrace with a sculpted pair of heron on the roof.

The small front garden was full of plants, closely tended, surrounding a rectangular patch of mown grass. Large windows gave passers-by a view right through the house into Jim’s rooms and to the Braid hills beyond. He never closed the shutters before nightfall. Sometimes before pulling the bell I hesitated, watching his careful movements, bent and slow, as he wrote at his desk. A tug on the cork sent the sprung bell swinging, chiming itself to a standstill.

Here was his last home, where he died in the Spring of his ninety fourth year, in his bed with three generations of offspring present.

After living in London, Paris, rural France, Morocco and Cambridge, he and his wife moved to his birthplace. Helen died in Jordan Lane; Jim spent his last years in Albert Terrace.

Jim opened his front door slowly. In his jacket and slippers he looked fine. Maybe his cheeks had white bristle but he wore an impeccable cravat, pinned by a silver brooch. He reached out both arthritic hands, held mine in greeting and smiled.

“Oh, you’re cold – come in.”

Into the hall with fresh flowers on a low wooden chest. From the blue curtain half-covering the door to his front room hung a cross on a thin chain – the George Cross, I think – usually hidden in folds. His feet shuffled as he led the way in and I stepped delicately, careful to enter respectfully. I took off my shoes and left them at the door.

He had explained how the space between furniture forms channels, a way of flowing. His bookcase could be a boulder around which paths split: so one walked through wide open doors and veered right, past plants and glass to a bedroom, or else swung left where the river narrowed into his tiny kitchen, with the cool still bathroom beyond… I was tender with these spaces, for clumsiness shows disrespect for the precision with which objects engage with each other, and with us. A pebble beside driftwood, and a candle holder on a cork – each found a meeting which could never be repeated. To pick up a brush was to enter its life; to place it again was another prayer. And in Jim’s hands everything found a place of true rest. Neither crowded nor lonely, but just where they seemed to belong.

This time I entered an especial stillness. Day was breaking, and the brightening thin blue sky’s light barely seeped inside. The air was warm, with the scent of pot pourri which filled an old wooden hatbox. Its rose petals came from Egypt, its lime blossom from Syria, and Jim flavoured it with French cognac.

Nothing moved except our arms in embrace. The fridge’s gentle hum was the only sound besides our breath, and my feet sliding in woollen socks on a smooth pine floor. I still carried some sleepiness and was glad to sit down – on a white-covered sofa beside rows of books. Lost Horizon by James Hilton, the Tao Te Ching, Saint John of the Cross and Winifred Rushforth’s Ten Decades of Happenings are the ones that I recall best.

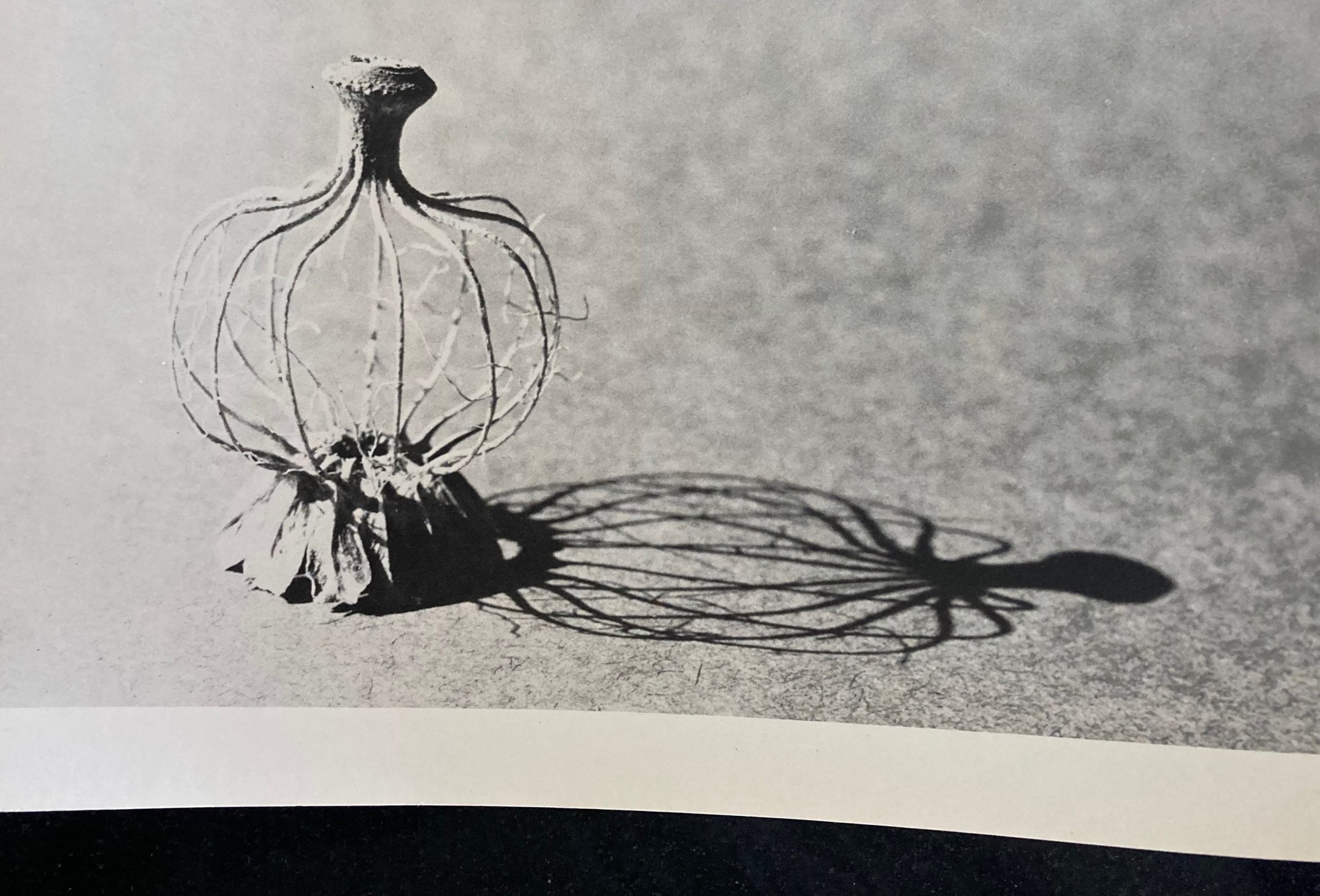

I looked through the glass tabletop, as I put down my china teacup beside a cactus, and saw the wavy grain in a brown stool. Under a cushion wrapped in tapestry I found a pale stone, smooth and oval, which fitted the hollow of my half-clenched palm.

“Please come to breakfast now,” he invited, leading the way into his bedroom. As he nudged open the door Tibetan prayer bells swung on the door handle and their high resonant note shocked me awake.

Jim’s bed was draped in folds of a soft cotton veil, amber against the white of his bedspread. It seemed as if no-one could ever have slept in that bed, he made it so perfectly every morning. Above the bed was a huge black-and-white photograph of a Fra Angelico in which an angel plays the harp strings of Christ’s radiating halo as He dies. Mary supports His limp body and weeps. The rigid form of Christ’s arm, torso and leg is angular – Cubist, in fact, Jim said.

At the foot of his bed hung a picture on hardboard above a yukka tree.The wood showed ages of weather, layers of paint and green stains. Onto the discarded board Jim had brushed black ink, making (for me that time) a movement of sails across rough sea. And above that began a high shelf, running round the entire room to the tall window. Along it were leaning porcelain plates, a soup tureen and some saucers, patterned in cool cream on predominant rich blue. This blue often returned to Jim when in India, sweating out a fever in tropical heat.

A terracotta Buddha sat in a corner, sheltered in a column of bark. Framed on the wall beside Buddha, a fine pencil landscape was so faint that I focussed on reflections in its glass. Then, concentrating, I discovered trees and clouds inside.

Before the window on an oblong mahogany table a feast was laid for two. Jim had peeled grapefruit segments and taken the seeds out of grapes to make fruit salad in delicate pale bowls pottered by Lucy Rie. A silver toast rack, a wooden butter dish, long thin hallmarked spoons to eat with, a sugarspoon-shell and a teapot were all composed as still life. Every object was a pleasure to look at and feel, and our food was delightful to taste. As we ate from this arrangement the composition came alive. The real beauty of his art, of the sculptures, crystals and flowers on our breakfast table, was how they gave life to ourselves as we breathed life into them.

The sky behind the Braid hills became vivid blue, brightened into yellow, then burned orange and gold as the sun rose up. A chorus of birdsong greeted the warm light which melted the frost on grass stalks and leaf tips. Our table swung into motion when long shadows fell in our laps. Sunlight warmed a smile inside me.

The sun lifted from the horizon with astonishing speed yet the shadows shortened and slid imperceptibly.

We talked of the past, of places Jim knew from a different age. He told me of Helen, how he had courted her love:

“I was an assistant at the Tate, an underling without parentage of much worth. She was a German who fitted in London society.” He was talking of the 1920s.

“I fell in love with her long before she noticed me. I wrote her letters – which she didn’t reply for some time – for seven years. Eventually I persuaded her that she loved me!” Jim paused and grinned, remembering the woman with whom he shared his life. They were married for over sixty years.

“I feel her presence sitting here in this room with me sometimes,” he whispered. And I thought I did, too.

He picked up a rough grey stone and it parted cleanly in his hands, showing a cavern of glittering crystal inside. “This,” he said, “may have been kicked open by a camel.” Leaving everything else to my imagination, he laid the open halves on the table.

We left the bedroom to sit on a sofa, now with strong sunshine on our backs. I saw a rainbow on the bookcase, cast by refraction through an octagonal glass beaker which scattered the sun’s light towering towards the skies.

When I left the house I moved into a different world, one where people were battling against cold wind, pressing forward to their places of work. I turned and saw Jim at the window, waving goodbye. I felt refreshed and awakened; come what may, I knew that this day had been blessed.

We have years of experience interviewing and writing. If you'd like to enquire about us writing your Legacy book for you or you'd like to learn how to write your own, please select from the options below.